What are Cohabitation Bonds?

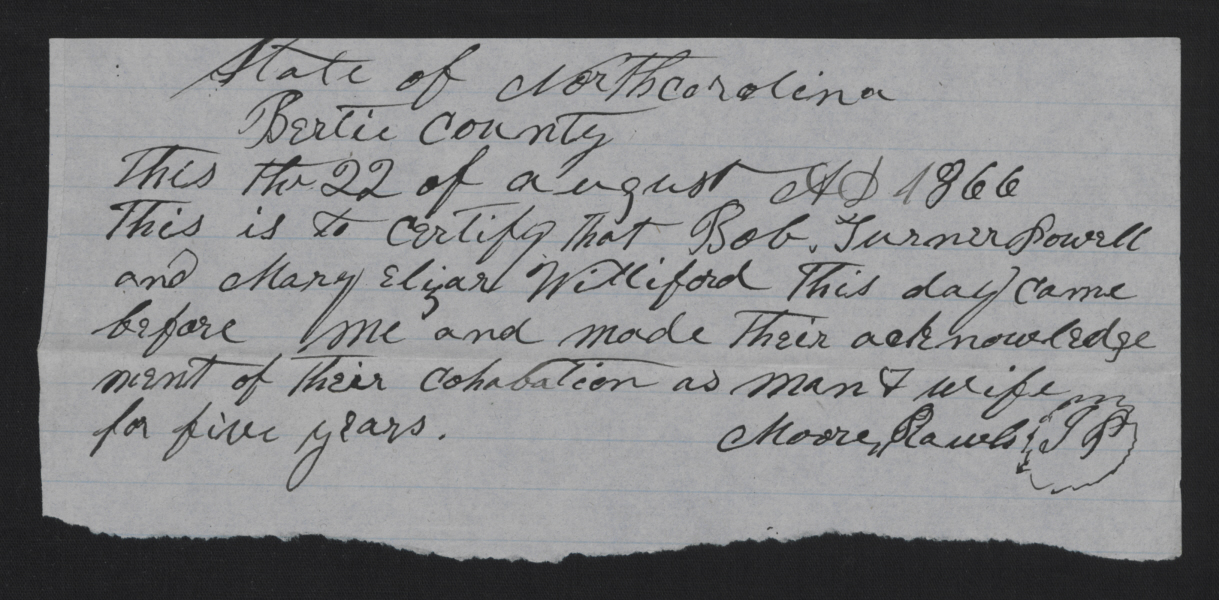

In 1866, a significant piece of legislation, “An Act Concerning Negroes and Persons of Color or of Mixed Blood,” changed the lives of many. It recognized that former enslaved people who had lived together as spouses during slavery were now legally married. These records, known as Cohabitation Bonds, were filed most often with the county Register of Deeds, and sometimes the Clerks of Superior Courts offices and held a retroactive effect, validating the marriages of countless formerly enslaved couples. Within these records, you’ll find names and ages of the bride and groom, the duration of their marriage, and in some counties, the name of their former enslaver and the number of children they had were also recorded. These surviving records do not represent all slave marriages by any means.

While these records are a treasure trove of historical insight, they also present some unique challenges. While in the original records cohabitation bonds are sometimes named as such, for many marriage records we cannot determine the race of the couple, therefore some county volumes may be digitized in their entirety. In these instances, white marriage records from 1866 may be included in the collection that do not specifically include the term “cohabitation”. Compliance with the law also varied, as not all couples came forward to acknowledge their unions; some continued to live as spouses under common law without formalizing their marriages through the new legal process. Moreover, the process of recording the surnames in these records reflected the era’s record-keeping habits, often depending on the discretion of the person documenting the information, the justice of the peace, with some counties having several different justice’s serving as witness. This led to variations in the accuracy of surnames or, in some cases, the absence of surnames altogether.

The counties of Catawba, Forsyth, Mecklenburg, Montgomery, New Hanover (CR.070.928.3), Robeson, and Wilkes (CR104.928.6) are not included in our digital Cohabitation Records Collection. These counties either require further research to confirm the presence of actual cohabitation bond records or are not housed at the State Archives and are unable to be located at the present time for further research. We also collaborated with the Register of Deeds offices in Caldwell County, Craven County, Davie County, Mitchell County, Union County, and Wayne County, borrowing volumes for our archival work. We have compiled a list of available and unavailable counties found in this collection below according to our records and those found in the index of cohabitation records, Somebody Knows My Name: Marriages of Freed People in North Carolina County by County, written by Barnetta McGhee White.

Exploring these Cohabitation Records provides not only insight into the legal and social changes of the post-Civil War period but also highlights the importance of critically analyzing historical documents. It reminds us of the challenges in interpreting records that were often created with limited resources and against the backdrop of a society grappling with profound societal shifts. Nonetheless, these records offer a valuable window into the past, revealing the enduring commitment and resilience of those who sought recognition and validation of their marriages during a transformative period in American history.

What are Cohabitation Bonds?

In 1866, a significant piece of legislation, “An Act Concerning Negroes and Persons of Color or of Mixed Blood,” changed the lives of many. It recognized that former enslaved people who had lived together as spouses during slavery were now legally married. These records, known as Cohabitation Bonds, were filed most often with the county Register of Deeds, and sometimes the Clerks of Superior Courts offices and held a retroactive effect, validating the marriages of countless formerly enslaved couples. Within these records, you’ll find names and ages of the bride and groom, the duration of their marriage, and in some counties, the name of their former enslaver and the number of children they had were also recorded. These surviving records do not represent all slave marriages by any means.

While these records are a treasure trove of historical insight, they also present some unique challenges. While in the original records cohabitation bonds are sometimes named as such, for many marriage records we cannot determine the race of the couple, therefore some county volumes may be digitized in their entirety. In these instances, white marriage records from 1866 may be included in the collection that do not specifically include the term “cohabitation”. Compliance with the law also varied, as not all couples came forward to acknowledge their unions; some continued to live as spouses under common law without formalizing their marriages through the new legal process. Moreover, the process of recording the surnames in these records reflected the era’s record-keeping habits, often depending on the discretion of the person documenting the information, the justice of the peace, with some counties having several different justice’s serving as witness. This led to variations in the accuracy of surnames or, in some cases, the absence of surnames altogether.

The counties of Catawba, Forsyth, Mecklenburg, Montgomery, New Hanover (CR.070.928.3), Robeson, and Wilkes (CR104.928.6) are not included in our digital Cohabitation Records Collection. These counties either require further research to confirm the presence of actual cohabitation bond records or are not housed at the State Archives and are unable to be located at the present time for further research. We also collaborated with the Register of Deeds offices in Caldwell County, Craven County, Davie County, Mitchell County, Union County, and Wayne County, borrowing volumes for our archival work. We have compiled a list of available and unavailable counties found in this collection below according to our records and those found in the index of cohabitation records, Somebody Knows My Name: Marriages of Freed People in North Carolina County by County, written by Barnetta McGhee White.

Exploring these Cohabitation Records provides not only insight into the legal and social changes of the post-Civil War period but also highlights the importance of critically analyzing historical documents. It reminds us of the challenges in interpreting records that were often created with limited resources and against the backdrop of a society grappling with profound societal shifts. Nonetheless, these records offer a valuable window into the past, revealing the enduring commitment and resilience of those who sought recognition and validation of their marriages during a transformative period in American history.

Popular Counties

Below is a list of available counties found in this digital collection. Each county includes their call number. Those that don't have a call number are more than likely the microfilm copy or were borrowed from the designated county's register of deeds office. Some counties may be listed twice; those may have a volume on microfilm only, while their physical materials (loose papers, volumes) may need further research before being scanned into the digital collection.

Call Number

|

County (A-Z) |

Available |

Unavailable |

| CR.003.928.1 | Alexander | Available | |

| CR.004.514.1 | Alleghany | Available | |

| CR.009.602.1 | Beaufort | Available | |

| CR.010.606.1 | Bertie | Available | |

| CR.012.604.1 | Brunswick | Available | |

| CR.013.925.2 | Buncombe | Available | |

| CR.014.301.12 | Burke | Unavailable | |

| (Loaned from Caldwell County) | Caldwell | Available | |

| Camden | Microfilm only | ||

| CR.019.602.001 | Carteret | Available | |

| CR.020.928.4 | Caswell | Available | |

| Catawba | Microfilm only | ||

| CR.021.928.3 | Catawba | (Needs further research) | |

| CR.024.602.1 | Chowan | Available | |

| Columbus | Microfilm only | ||

| (Loaned from Craven County) | Craven | Available | |

| CR.029.928.3 | Cumberland | Available | |

| CR.030.301.9 | Currituck | Available | |

| CR.032.928.16 | Davidson | Available | |

| (Loaned from Davie County) | Davie | Available | |

| Duplin | Microfilm only | ||

| CR.037.603.1-2 | Edgecombe | Available | |

| Forsyth | Microfilm only | ||

| Forsyth | (Needs further research) | ||

| CR.039.603.1 | Franklin | Available | |

| CR.041.928.5 | Gates | Available | |

| CR.044.928.1-3 | Granville | Available | |

| CR.045.928.6 | Greene | Available | |

| CR.046.602.1 CR.046.928.5 | Guilford | Available | |

| CR.047.928.4 | Halifax | Available | |

| CR.053.603.1 CR.053.928.3 | Hyde | Available | |

| CR.054.602.1 | Iredell | Available | |

| CR.056.603.1 | Johnston | Available | |

| CR.060.928.1 | Lincoln | Available | |

| CR.061.928.4 | Macon | Available | |

| Mecklenburg | Microfilm only | ||

| (Loaned from Mitchell County) | Mitchell | Available | |

| CR.067.602.1 | Montgomery | Unavailable | |

| CR.069.603.1 | Nash | Available | |

| CR.070.603.1-3 | New Hanover | Available | |

| CR.070.928.3 | New Hanover | (Needs further research) | |

| CR.073.603.1 | Orange | Available | |

| CR.075.603.1 | Pasquotank | Available | |

| CR.077.928.6 | Perquimans | Available | |

| Perquimans | Microfilm only | ||

| CR.078.603.1 | Person | Available | |

| CR.079.603.1 | Pitt | Available | |

| CR.082.602.1 CR.082.603.1 | Richmond | Available | |

| CR.83.928.2-5 | Robeson | (Needs further research) | |

| Robeson | Microfilm only | ||

| Rowan | Microfilm only | ||

| CRX.250 | Sampson | Available | |

| CR.090.603.1 CR.090.928.2 | Stokes | Available | |

| CR.092.602.1 CR.092.928.4 | Surry | Available | |

| (Loaned from Union County) | Union | Available | |

| CR.099.603.1 | Wake | Available | |

| CR.100.602.1 | Warren | Available | |

| CR.101.603.1 | Washington | Available | |

| (Loaned from Wayne County) | Wayne | Available | |

| CR.104.606.1 | Wilkes | Available | |

| CR.104.928.6 | Wilkes | (Needs further research) | |

| Wilson | Microfilm only |

List of Available Counties

Below is a list of available counties found in this digital collection. Each county includes their call number. Those that don't have a call number are more than likely the microfilm copy or were borrowed from the designated county's register of deeds office. Some counties may be listed twice; those may have a volume on microfilm only, while their physical materials (loose papers, volumes) may need further research before being scanned into the digital collection.

Call Number

|

County (A-Z) |

Available |

Unavailable |

| CR.003.928.1 | Alexander | Available | |

| CR.004.514.1 | Alleghany | Available | |

| CR.009.602.1 | Beaufort | Available | |

| CR.010.606.1 | Bertie | Available | |

| CR.012.604.1 | Brunswick | Available | |

| CR.013.925.2 | Buncombe | Available | |

| CR.014.301.12 | Burke | Unavailable | |

| (Loaned from Caldwell County) | Caldwell | Available | |

| Camden | Microfilm only | ||

| CR.019.602.001 | Carteret | Available | |

| CR.020.928.4 | Caswell | Available | |

| Catawba | Microfilm only | ||

| CR.021.928.3 | Catawba | (Needs further research) | |

| CR.024.602.1 | Chowan | Available | |

| Columbus | Microfilm only | ||

| (Loaned from Craven County) | Craven | Available | |

| CR.029.928.3 | Cumberland | Available | |

| CR.030.301.9 | Currituck | Available | |

| CR.032.928.16 | Davidson | Available | |

| (Loaned from Davie County) | Davie | Available | |

| Duplin | Microfilm only | ||

| CR.037.603.1-2 | Edgecombe | Available | |

| Forsyth | Microfilm only | ||

| Forsyth | (Needs further research) | ||

| CR.039.603.1 | Franklin | Available | |

| CR.041.928.5 | Gates | Available | |

| CR.044.928.1-3 | Granville | Available | |

| CR.045.928.6 | Greene | Available | |

| CR.046.602.1 CR.046.928.5 | Guilford | Available | |

| CR.047.928.4 | Halifax | Available | |

| CR.053.603.1 CR.053.928.3 | Hyde | Available | |

| CR.054.602.1 | Iredell | Available | |

| CR.056.603.1 | Johnston | Available | |

| CR.060.928.1 | Lincoln | Available | |

| CR.061.928.4 | Macon | Available | |

| Mecklenburg | Microfilm only | ||

| (Loaned from Mitchell County) | Mitchell | Available | |

| CR.067.602.1 | Montgomery | Unavailable | |

| CR.069.603.1 | Nash | Available | |

| CR.070.603.1-3 | New Hanover | Available | |

| CR.070.928.3 | New Hanover | (Needs further research) | |

| CR.073.603.1 | Orange | Available | |

| CR.075.603.1 | Pasquotank | Available | |

| CR.077.928.6 | Perquimans | Available | |

| Perquimans | Microfilm only | ||

| CR.078.603.1 | Person | Available | |

| CR.079.603.1 | Pitt | Available | |

| CR.082.602.1 CR.082.603.1 | Richmond | Available | |

| CR.83.928.2-5 | Robeson | (Needs further research) | |

| Robeson | Microfilm only | ||

| Rowan | Microfilm only | ||

| CRX.250 | Sampson | Available | |

| CR.090.603.1 CR.090.928.2 | Stokes | Available | |

| CR.092.602.1 CR.092.928.4 | Surry | Available | |

| (Loaned from Union County) | Union | Available | |

| CR.099.603.1 | Wake | Available | |

| CR.100.602.1 | Warren | Available | |

| CR.101.603.1 | Washington | Available | |

| (Loaned from Wayne County) | Wayne | Available | |

| CR.104.606.1 | Wilkes | Available | |

| CR.104.928.6 | Wilkes | (Needs further research) | |

| Wilson | Microfilm only |

According to the cohabitation index, Somebody Knows My Name: Marriages of Freed People in North Carolina County by County, researched and written by Barnetta McGhee White, the following list contains counties for which no cohabitation records have been found.

| Alamance | Cherokee | Hertford | McDowell | Rockingham |

| Anson | Cleveland | Jackson | Mecklenburg | Stanly |

| Ashe | Gaston | Jones | Montgomery | Tyrrel |

| Bladen | Harnett | Lenoir | Moore | Watauga |

| Cabarras | Haywood | Madison | Onslow | Yadkin |

| Chatham | Henderson | Martin | Polk | Yancey |

Counties Without Cohabitation Records

According to the cohabitation index, Somebody Knows My Name: Marriages of Freed People in North Carolina County by County, researched and written by Barnetta McGhee White, the following list contains counties for which no cohabitation records have been found.

| Alamance | Cherokee | Hertford | McDowell | Rockingham |

| Anson | Cleveland | Jackson | Mecklenburg | Stanly |

| Ashe | Gaston | Jones | Montgomery | Tyrrel |

| Bladen | Harnett | Lenoir | Moore | Watauga |

| Cabarras | Haywood | Madison | Onslow | Yadkin |

| Chatham | Henderson | Martin | Polk | Yancey |

Related Collection: Voter Registration

Ratified in 1870, the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution guaranteed that the right to vote could not be denied because of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Multiple Southern U.S. states found ways around this amendment by creating their own amendments with new requirements for voters. This excluded African American men, and some white male voters. To solve the disenfranchisement of white males, North Carolina enacted the “grandfather clause” also known as the Permanent Registration of Voters resulting in the creation of voter registries from 1902 to 1908, organized by county. The information collected includes the voter registrants' name and age, their qualifying ancestor and their home state, and the date of registration.The Voter Registration digital collection is an ongoing project, and additional items will be added as they are digitized.